Click on articles and images for full view in separate tab.

Please hold screen horizontally when viewing on phone.

—–

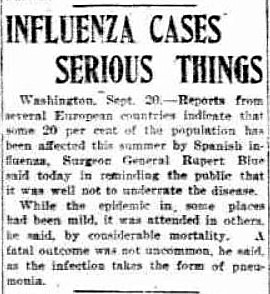

Looking back, reading reports in local newspapers from the fall of 1918 through the lens of hindsight, you can see it coming: a deadly wave, at first so distant on the horizon it must have seemed barely worth noting, but each day growing stronger, spreading wider, coming closer to Genesee County.

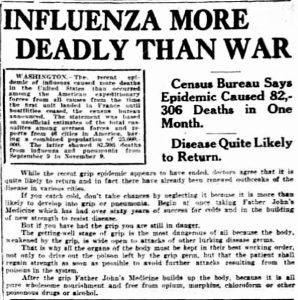

Ultimately, the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 and early 1919 would infect at least a third of the global population, and kill an estimated 50 to 100 million people worldwide. In the United States, more than 650,000 Americans died.

But in those opening fall days in Genesee County, the handful of minor items in the papers reporting flu and pneumonia outbreaks in Europe and in Boston seemed little cause for alarm.

And what was so new about the flu, anyway? Every fall and winter had brought influenza, also known as the grippe. Most victims spent several unpleasant days in bed with body aches and fever and then recovered.

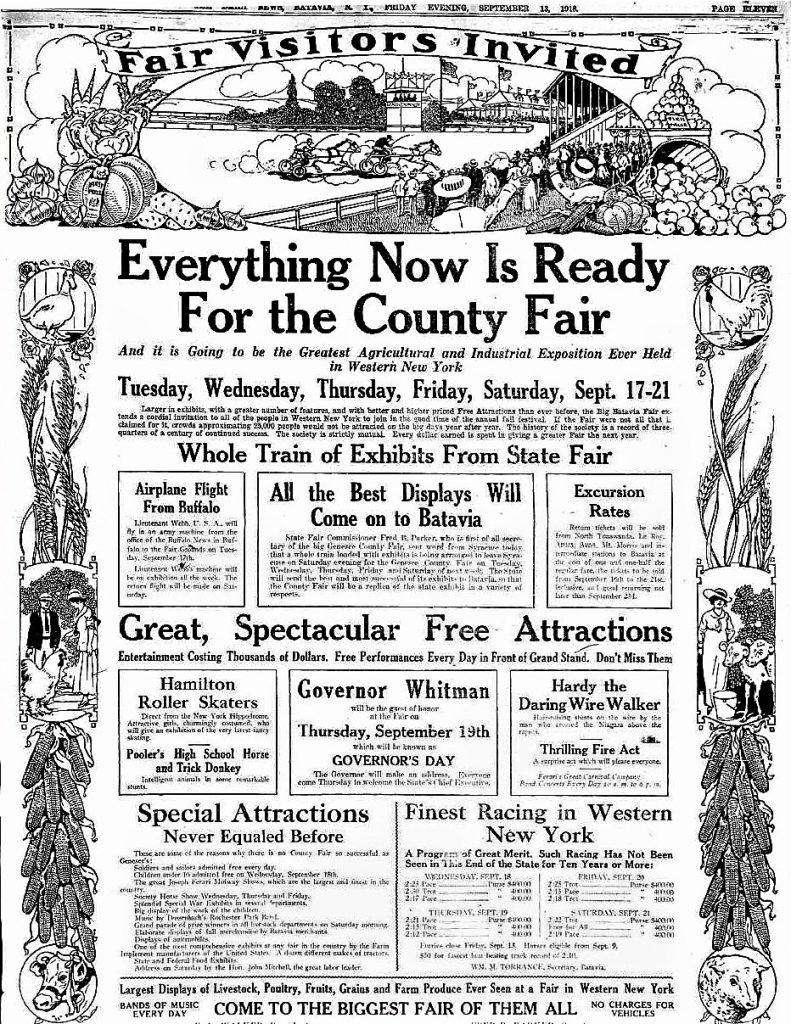

Besides, it was the year’s fairest and busiest season. The trees were afire in leafy color. It was harvest time. Crowds were flocking to the county fair.

Even the news from “over there” was heartening. American and Allied forces were pushing the Kaiser back on all fronts. The Huns were on the run. There was talk that the war would soon be over.

But the onrushing wave gathered speed.

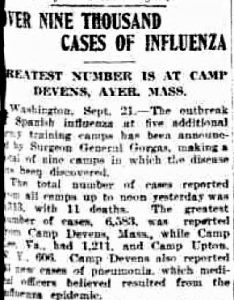

September 21, 1918 Batavia Daily News

September 21, 1918 Batavia Daily News

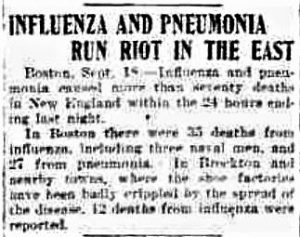

On the same day the county fair ended, the Batavia Daily News reported thousands of influenza and pneumonia cases at Army training camps.

“The total number of cases reported from all camps up to noon yesterday was 9,313, with 11 deaths.”

Less than a week later, similar outbreaks had occurred among civilians in New York City, Philadelphia, and other population centers — and were spreading into rural areas. Reports in local newspapers grew more urgent.

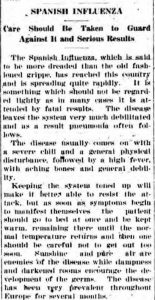

September 25, 1918 LeRoy Gazette-News

September 25, 1918 LeRoy Gazette-News

“The Spanish Influenza, which is said to be more dreaded than the old fashioned grippe, has reached this country and is spreading quite rapidly. It is something which should not be regarded lightly as in many cases it is attended by fatal results. The disease leaves the system very much debilitated and as a result pneumonia often follows.”

But the warnings told only part of the story. Physicians and scientists were finding, to their puzzlement and horror, that this flu behaved like no other.

Many patients displayed startling symptoms. Their lips turned black, their faces blue; their noses hemorrhaged, their throats gurgled with fluids. Autopsies of victims revealed lungs choked with bloody mush.

The flu and its most common complication, severe pneumonia, were so frequently intertwined it was nearly impossible for doctors to distinguish which was the actual cause of death. The disease spawned other grave conditions, too: childbirth complications, kidney and heart failure, diphtheria, tuberculosis, meningitis.

Most perplexing: this flu, unlike previous strains, attacked healthy young adults with particular ferocity. Hale and hearty individuals in the prime of life with no prior medical problems—men and women between the ages of twenty and forty-something—seemed especially vulnerable. Many died within days, or even hours, of first developing symptoms.

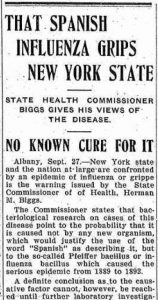

September 28, 1918 Batavia Times

September 28, 1918 Batavia Times

As September drew to a close, New York State health officials issued a warning that the epidemic was spreading throughout the state . . . and the nation at large.

“There is no known cure.”

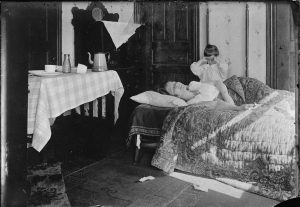

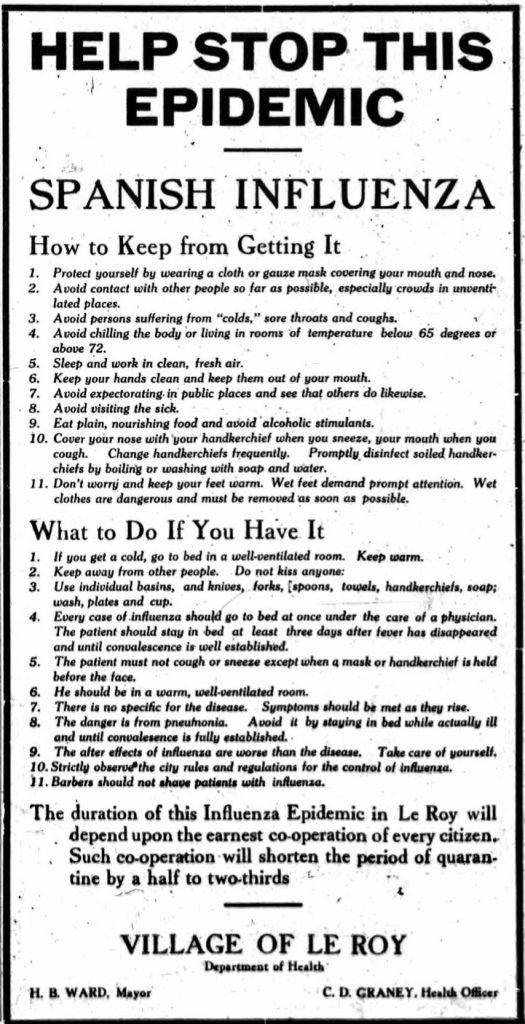

Physicians were at a loss. There were no influenza vaccines, no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections such as pneumonia. Doctors could merely treat the symptoms, and advise patients to stay in bed, stay warm, and drink lots of liquids.

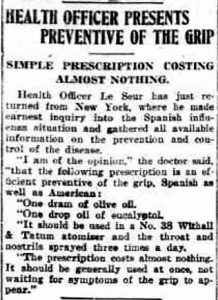

Some physicians, including Dr. J.W. Le Seur, Batavia’s health officer, prescribed a homemade preventive spray:

“One dram of olive oil. One drop oil of eucalyptol . . . the throat and nostrils [should be] sprayed three times a day”

But nothing stopped the wave.

In October, it struck Genesee County full force.

Bergen was the first to feel the brunt.

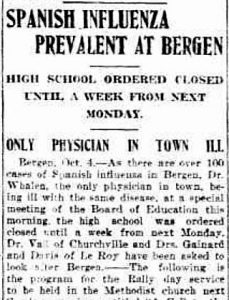

October 4, 1918 Batavia Daily News

October 4, 1918 Batavia Daily News

“As there are over 100 cases of Spanish influenza in Bergen, Dr. Whalen, the only physician in town, being ill with the same disease . . . the high school was ordered closed . . . . Drs. Ganiard and Davis of LeRoy have been asked to look after Bergen.”

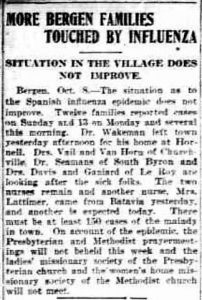

October 8, 1918 Batavia Daily News

October 8, 1918 Batavia Daily News

Four days later, the situation had only grown worse. More doctors and nurses were called in.

“Twelve families reported cases on Sunday and 13 on Monday and several this morning. There must be at least 150 cases of the malady in town.”

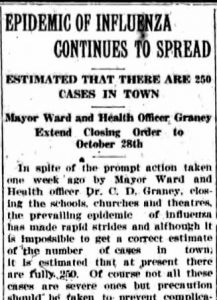

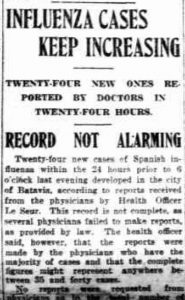

Cases were being reported in other county towns, too. Officials attempted to allay the public’s growing fears. Batavia’s health officer assured city citizens that relatively few cases of flu had appeared, and nearly all were “mild.”

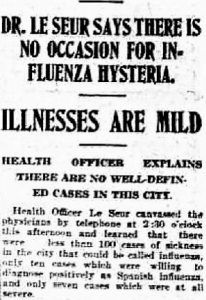

October 10, 1918 Batavia Daily News

“Health Officer Le Seur . . . learned there were less than 100 cases of sickness in the city that could be called influenza . . . and only seven cases which were at all severe.”

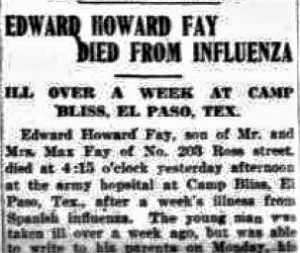

But also on the front page of that day’s Daily News came the first announcement of the death of a Genesee County serviceman from Spanish influenza: 20-year-old Edward Howard Fay of Byron had succumbed at Camp Bliss, Texas. Before the war was over, 13 others in service from Genesee County would die from the disease or its complications.

But also on the front page of that day’s Daily News came the first announcement of the death of a Genesee County serviceman from Spanish influenza: 20-year-old Edward Howard Fay of Byron had succumbed at Camp Bliss, Texas. Before the war was over, 13 others in service from Genesee County would die from the disease or its complications.

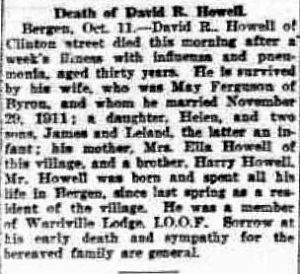

The next day, October 11, 1918, area physicians recorded the county’s first four deaths from Spanish influenza and its complications.

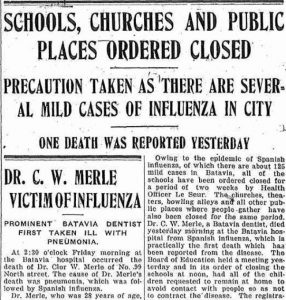

One was Dr. Merle Clor, a 29-year-old Batavia dentist with a young wife and a two-year-old daughter.

Two were farmers—David R. Howell, age 30, from Bergen, and Lynne V. Parsons, 32, of Le Roy. Both men were married with young children.

The fourth victim was Miss Martha Ganiard, the 16-year-old daughter of Dr. Henry Ganiard—one of the Le Roy physicians who’d been traveling regularly to Bergen to care for flu patients while the town’s own doctor was also incapacitated by the disease.

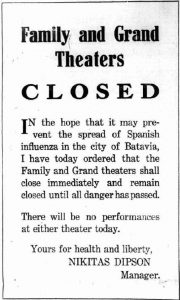

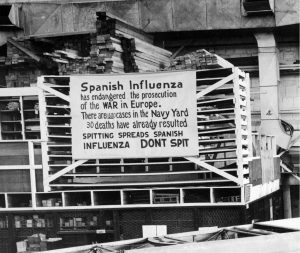

On that same day, because so many new cases were appearing, Batavia’s health officer ordered all schools, churches, theaters, bowling alleys, and other gathering places closed for two weeks.

Officials in Bergen and LeRoy had already issued similar closing orders. Elba, Corfu, Darien, Oakfield and other county towns would follow suit.

Public notices appeared in newspapers pleading with the public to take every possible measure to prevent further spread of the deadly disease.

But the numbers of cases soared. Hundreds of Genesee County men, women, and children were ill with influenza. Often, entire households were stricken, leaving no one to care for fellow family members. Few homes escaped the illness entirely.

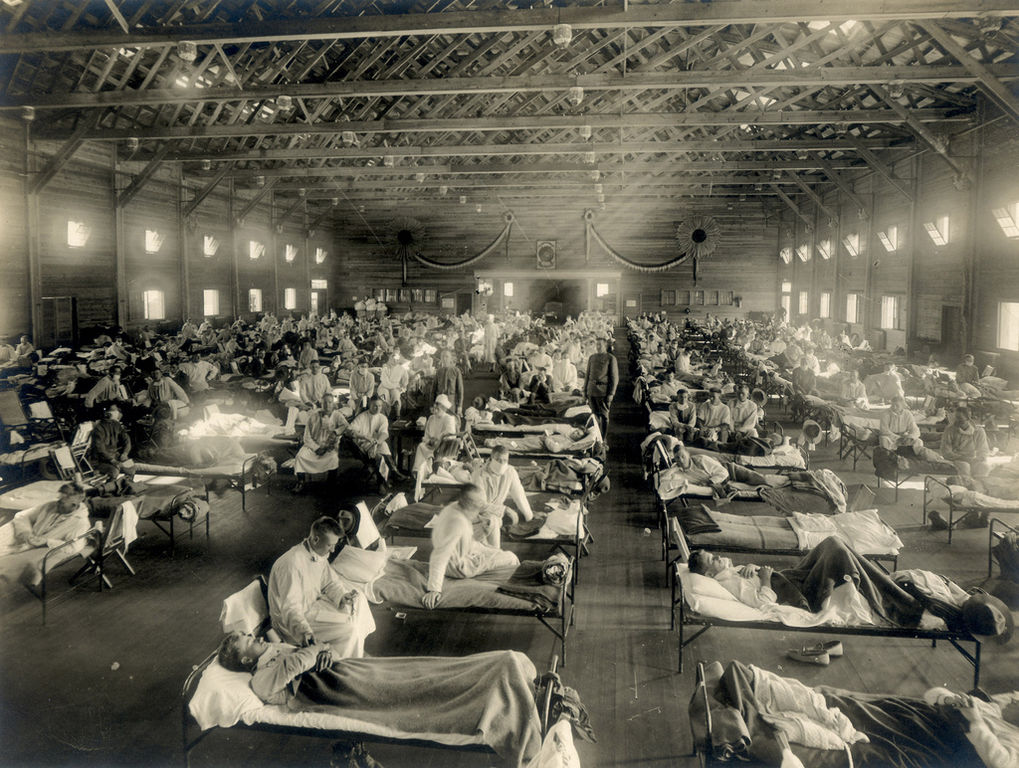

Doctors and nurses were overwhelmed. Hospitals were inundated with patients.

Every day brought more cases—and more deaths.

Within one week after the first four had died in the county, 27 more had perished from Spanish flu and/or pneumonia.

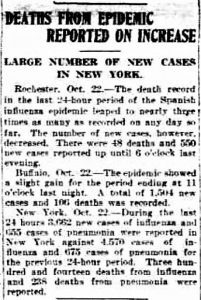

Businesses were suffering. Customers and employees were staying at home; some because they were sick, others out of fear of becoming so.

Factories closed for lack of workers well enough to do their jobs.

Crops ready for fall harvest were rotting in the fields.

“Help is very scarce and there are many beans unharvested and acres of potatoes which are not dug,” came an October 16, 1918 report from Bergen in the Batavia Daily News.

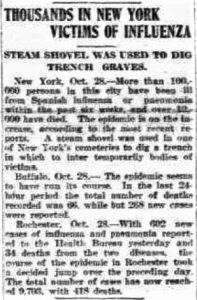

Daily updates giving the numbers of cases and deaths reported in Rochester and Buffalo over the previous 24 hours were alarming. The numbers for New York City were staggering.

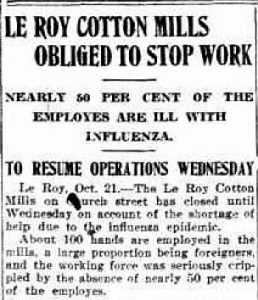

October 22, 1918 Batavia Daily News

October 22, 1918 Batavia Daily News

[Rochester] “There were 48 deaths and 550 new cases reported up until 6 o’clock last evening.”

[Buffalo] “. . . for the period ending at 11 o’clock last night . . . a total of 1,504 new cases and 106 deaths was recorded.”

Determined to stem the tide in Genesee County, most towns continued to keep their schools closed, and to ban or at least discourage public gatherings.

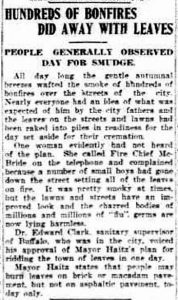

Batavia officials went a step further, announcing a “Smudge Day” to fight the disease. All citizens were to rake up their leaves into piles and burn them en masse on the designated day. The carbon and smoke, officials said, would kill the influenza “germs.”

October 24, 1918 Batavia Daily News

October 24, 1918 Batavia Daily News

Despite objections that the smoke would only worsen the conditions of flu and pneumonia patients already struggling to breathe, the plan was carried out.

“All day long the gentle autumnal breezes wafted the smoke of hundreds of bonfires over the streets of the city . . . . It was pretty smoky at times, but . . . the streets have an improved look and the charred bodies of millions and millions of ‘flu’ germs are now lying harmless.”

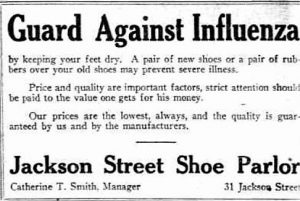

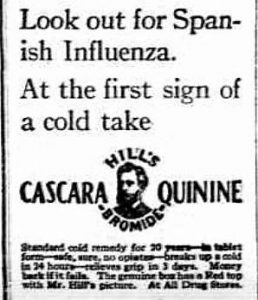

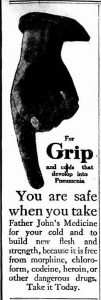

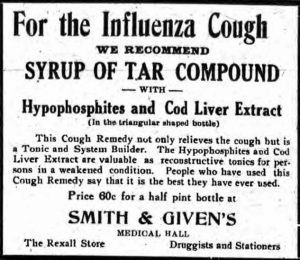

The burning, of course, did no more to deter Spanish influenza than the many potions, tonics, and other patent medicines (even shoes!) that were touted as preventives and cures in local newspaper ads.

The burning, of course, did no more to deter Spanish influenza than the many potions, tonics, and other patent medicines (even shoes!) that were touted as preventives and cures in local newspaper ads.

54 more people in Genesee County died during the second week following the first fatalities.

Nothing stopped the disease. Every day brought a flood of additional cases—and more tragic fatalities.

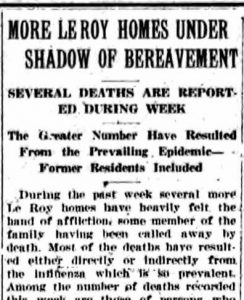

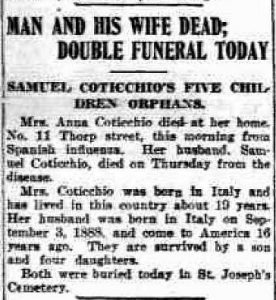

Obituaries and funeral announcements filled the pages of local newspapers.

So did stories of multiple deaths in families, of parents losing beloved children, and of children suddenly orphaned.

The bad news, both local and otherwise, kept coming.

It seemed the horror would never end.

October 28, 1918 Batavia Daily News

October 28, 1918 Batavia Daily News

[New York] “More than 100,000 persons in this city have been ill from Spanish influenza within the past six weeks, and over 12,000 have died.”

[Rochester] “The total number of cases has now reached 9,703, with 418 deaths.”

——

By the end of October, in just 20 days—from the first death report on the 11th to the close of the month on the 31st—116 Genesee County men, women, and children had died of influenza and/or pneumonia or other complications of the disease.

By November 11, when Germany at last agreed to lay down its arms, ending the war, 19 more had perished. The remaining weeks of November would take two dozen additional lives, bringing the total fatalities in Genesee County for the two months to 159.

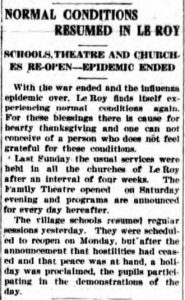

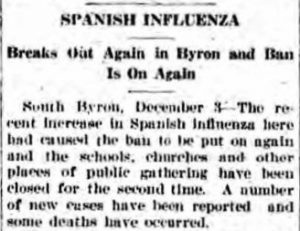

Gradually throughout November, however, the numbers of cases in Genesee County steadily decreased. . . and with that decline, the numbers of deaths diminished as well. Bans of public gatherings were lifted. Schools and churches reopened.

Although December 1918 and early 1919 would bring sporadic additional outbreaks, and deaths, the fall of 1918 would prove to have been the peak of the disease.

The worst, like the war, was over.

——

Today, mysteries remain over the origin, causes, and nature of the devastating flu. We understand now that in the spring of 1918 a lesser wave of the same flu had broken out in isolated pockets in the United States, particularly in Army camps, as well as among troops of all countries overseas. But the lack of disease-reporting agencies at home, and strict censorship of bad news by armies on all sides of the war, prevented a coordinated medical response, and kept the general public in the dark.

Only in Spain, a neutral country without censorship, was the disease widely reported—thus giving it the inaccurate name of “Spanish” influenza.

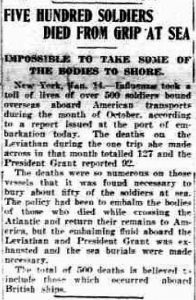

The truth was that throughout 1918 all the armies in the war were ravaged by the disease, reducing many units to a small fraction of their effective combat strength, and creating a demand for more replacements, more men who in turn would be exposed to the flu while crammed into close quarters in camps, barracks, navy yards, and troopships. Tens of thousands of soldiers died from the disease and its complications.

Scientists today have identified the 1918 virus as an H1N1 subtype with distinctive mutations. But despite replicating and studying the microbe, medical experts still don’t fully understand its uniquely devastating properties, its penchant for the young and healthy, its mechanisms for rapidly ravaging bronchial tubes and lungs and damaging other organs.

Clearly, however, one major cause of the disease’s deadly global spread was the war itself—or more specifically, the vast movements of troops from all over the world on land and sea, often in conditions that served as virtual incubators. The virus’s dispersion into civililan populations was only a matter of time.

In a sense then, every victim of the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 to 1919 was a casualty of World War I.

The influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 killed three to five percent of the world’s population. In less than two years, it took more American lives than all U.S. wars of the past century combined.

Perhaps the pandemic’s greatest mystery is this: Why has one of the most cataclysmic public-health disasters in human history been largely relegated to the distant shadows of our national memory?

Have we forgotten the many who died?

Next: Part 2—Remembering the Victims of Genesee County’s Autumn 1918 Spanish Influenza Epidemic

Resources

All Genesee County death statistics from A Special Report on the Mortality from Influenza in New York State During the Epidemic of 1918-19 by Otto R. Eichel, M.D., New York State Department of Health, New York 1923 (pages 24-27). Accessed online, https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=ZdQ3AAAAIAAJ&hl=en

National and worldwide statistics based on “1918 Pandemic (H1N1 Virus)” website, Centers for Disease Control, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html

Credits

Genesee County in Autumn photo, ©2017 Terry Krautwurst; “Keep ‘Em Going, Boy!”, author collection; “Emergency Influenza Hospital at Camp Funston, Kansas, 1918,” Otis Historical Archives Nat’l Museum of Health & Medicine [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons; “National Red Cross Home Service Photo, 1918,” retrieved from the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2017668532/); “Influenza Precaution Sign” [NH 41731-A], Naval History and Heritage Command (https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography.html).

Newspaper articles and ads retrieved from fultonhistory.com.

This article was sobering. I never knew of the severity of this epidemic – only heard bits and pieces of this Spanish flu over the years. I feel fortunate to live in LeRoy during the current pandemic. So many were hit in our little village in 1918-19. Hope everyone reads this amazing post❤️

Thanks for reading, Joan, and for your kind words.

My grandmother’s younger sister, Estelle (Stella) Hoffman died in the Spanish Flu epidemic. The Hoffman family lived in LeRoy, Genesse County. Several members of the Hoffman and Sandles families were affected. My husband and I stayed in LeRoy for two days two summers ago so I could see the town where my Grandmother grew up. I spent a morning at the beautiful cemetery on the banks of Oatka Creek. I found the family graves and left roses. I stood there thinking of my family members and their friends and neighbors who returned over and over to bury folks they loved. Stella had no headstone, but the record showed she was buried beside her mother. I was told that there were so many deaths at that time, they were just burying people and some families didn’t even have money for a headstone.

Thanks for this site!

Diane, Thank you so much for your comments, and for your lovely descriptions of LeRoy’s Machpelah Cemetery and the sadness of the times. Your grandmother’s sister, Stella Hoffman, died of influenza on December 28, 1918, less than a week after contracting the disease. She was only 19 years old. At the time, both of her brothers, also from LeRoy, were away, serving in the Army.